Randi McGinn tilts at windmills - and often knocks them down

Kent Walz / Editor-in-Chief, Albuquerque Journal - https://www.abqjournal.com/991874/sending-messages.html/amp

It’s International Women’s Day but Albuquerque lawyer Randi McGinn isn’t taking part in the “don’t show up for work” part of the event.

Out of the office, Randi McGinn likes buying and restoring houses. “You take something that’s a mess and you straighten it out,” she says as she exits a Downtown home she’s renovated. (Marla Brose/Journal)

Not because she’s not a believer, but because “I can do more good here at the office, and I do have my red,” she says as she gives a tour of her law firm’s spacious, sun-drenched offices adorned with what she describes as “women’s empowerment art” – a collection that includes a colorful painting of the five partners, all women, that dominates one of the conference rooms.

Besides, you don’t need to burnish your gender credentials when you are one of three women members of the Inner Circle of Advocates, which describes itself as an “organization of 100 of the best plaintiff lawyers in the United States.” You don’t “join” the Inner Circle. It’s invitation only – and that invite requires multiple million-dollar jury verdicts.

A photo from the 1970s shows Randi McGinn and escort at her high school prom in Alamogordo. (Courtesy of Randi McGinn)

Most New Mexicans probably don’t know McGinn as a top-tier plaintiff’s lawyer, but as the special prosecutor who agreed – “because nobody else would” – to take to trial the case of two Albuquerque Police Department officers charged with murder in the shooting death of a mentally ill, homeless camper with a long rap sheet.

Few know that in the early 1980s as a relatively fresh-out-of-law school assistant district attorney she put a man on death row for killing an APD officer, and not many outside the legal system know about the successful legal career that has made her one of America’s top civil trial lawyers.

It’s an area where McGinn, 61, stands out because so few women of her generation followed that path.

So what allowed this one-time Alamogordo cowgirl turned newspaper reporter to excel at convincing juries?

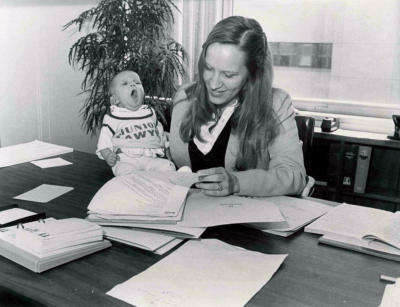

Lawyer Randi McGinn, with daughter Heather McGinn by her side, works in the District Attorney’s Office in 1981. (Courtesy of Randi McGinn)

For starters, she says she chooses not to be afraid.

And there is the storytelling ability she traces to her reporter roots, and the personality gene.

“I just have an optimistic personality. I can’t take credit. I think it’s just how you’re born. So even when knocked for a loop I bounce back pretty quickly.”

The most important trait could well be dealing with defeat – something she says a lot of females didn’t get practice with because they didn’t have the opportunity to participate in sports.

“When I was in law school (in the late ’70s at the University of New Mexico), half our class was women and maybe a dozen wanted to be litigators. Now hardly any are. You know when those women quit? When they lost a case. And that makes sense for my generation because the only place we could compete was in class. Girls didn’t get to play sports (often the exception in life, McGinn fought to play on the boys tennis team at Alamogordo High School).

“Girls could cheer and do drill, and I did that, but in sports you learn that some days no matter how good you are, the wind blows the wrong way and even if you play over your head you lose.

“We didn’t learn how to lose. Women lost a case and thought it meant there was something wrong with them. As a trial lawyer you have to be able to lose and pick yourself up and go out the next day and fight again.”

Passionate about work

McGinn didn’t get a conviction in last year’s trial of the two APD officers. The case ended in a mistrial and she says she is fine with the result and the message sent to police and to the community.

Most of the corporations and other defendants in her cases haven’t fared as well.

“I’ve had 130 trials and think I’ve lost six. Don’t get me wrong. I hate losing. But I understand why even if I don’t agree.”

Asked to cite her biggest professional disappointment she replied, “It’s hard to say because even when they happen they don’t last long.”

She is passionate about her work and quick to engage when asked about a couple of her cases during an hour-long interview.

Not surprisingly, she views those cases as “sending messages.”

One centered on Elizabeth Garcia, a divorced mother of three who was working alone on the graveyard shift at a Hobbs-area convenience store when she was kidnapped, sexually assaulted and stabbed 56 times in 2002. It was her second day on the job, according to news reports.

Approaching the case like the reporter she once was, McGinn and her colleagues used shoe leather and public records laws to dig into police reports from towns where the multi-state chain operated hundreds of stores.

“We found 13 people killed at these stores who were working alone. There were 1,200 reports where people had been attacked, raped, etc. We proved (the inadequate security) was a calculated way to make money.”

The case against the convenience store chain was settled confidentially while the jury was out and McGinn concedes it was for less than the $50 million the jury would have awarded. But it was enough to send a message to corporate ownership and to take care of Elizabeth Garcia’s family. As important, the case led to rules governing the convenience store industry that included requiring either two people on duty, bullet-resistant glass or closing after a certain time.

Regulators held hearings around the state before adopting the rules and McGinn was front and center.

“We mobilized those who had lost loved ones” and there were more than a dozen lobbyists on the other side, she said. “Some lobbyist with a big old diamond ring came up and said, ‘I want to know who is paying you.’ I said, ‘Nobody is paying us. We were just doing the right thing.'”

“Those are the kind of cases I like best,” she said, “where you have an army of lawyers and lobbyists on the other side.”

Pacemaker

The lawsuit against a southern New Mexico cardiologist and hospital for implanting pacemakers that patients didn’t need is another where the already energetic McGinn ramps up a notch as she talks about it.

“This guy would literally troll the ER. Somebody might be there with a hurt knee and he would stop and suggest an EKG and tell the patient he needed a pacemaker. The patient might say I didn’t even know I had a heart problem so maybe I should get a second opinion.

“The doctor would say, well you could but before you leave I’d like you to sign this paper saying you understand you could die on the drive home.”

Between the implants and cath lab procedures, the hospital probably did $50 million in pacemaker business in five years. “And everybody knew. Other docs wouldn’t let this guy take calls for their patients. The cath lab complained. It’s a classic case of follow the money. It’s what almost always drives this bad behavior.”

The jury found for the plaintiffs, awarding $67 million – an amount that was later reduced by the judge.

Coming up: The lawsuit against Motel Six by former CNN journalist Lynn Russell and her husband, who ended up in a gunfight with assailants they said were trying to rob them at the Albuquerque motel where they had stopped on their way to California.

“They cater to people who might be vulnerable to attack,” she said of the chain, referring to the company’s “leave the light on for you” slogan.

Like the convenience store case, this will be about a major corporation’s security measures.

Woman in court

So has McGinn found the courtroom to be hostile to women?

To the contrary.

“I think being a woman is an advantage. I don’t look like everybody else. I don’t look like guys in suits talking to the jury in this highfalutin’ language,” she said. “Jurors are going to gravitate towards me so I can explain stuff to them.”

For example?

She says a male juror once interrupted opposing counsel who was making repeated objections by blurting out, “you just leave her alone.” An older woman juror reached and patted her on the arm during closing argument. Another jury bought her a gift they presented after the trial – “these little gaiters to keep my sweater sleeves up. It was the cutest thing ever.”

Be yourself

It all flowed naturally for McGinn as a trial lawyer after she decided to “be who I am.”

“There weren’t many women trial lawyer models in the early 1980s so at first I wore severe suits and those fakey girl ties and had my hair in a severe bun. Then I decided that just wasn’t me and I went to sweaters and dresses.”

And she says she was one of the first to use PowerPoint in trial.

It’s about relating to the jury, she says, and telling your story in effective ways.

NM transplant

McGinn’s father was in the military and hers was what she describes as a lower middle class family where you ate the same meal on each week night – taco Tuesday, meatloaf Wednesday – and a lot of canned veggies.

They moved from southern California to Alamogordo when she was in high school.

“I came from a school with 4,000 kids. I was a SoCal girl and did Valley girl speak. Driving out I remember desert and dead jackrabbits and we had a house right on the edge of the base, no fence or anything. I remember opening the sliding glass door and thinking … my life is so over.”

“But in truth it was probably a good thing because I was a mischievous child.

“In Alamo we plotted to steal the big hamburger boy outside the A&W. If I had done that in LA I could have ended up in a dark cell and had a different career. In Alamo they don’t call the cops, they call your parents and say your daughter has stolen the Big Boy and should bring it back – which we did after homecoming parade.”

After Alamogordo, where she learned to be a real horse-riding cowgirl, she went to New Mexico State University where she majored in journalism and government – and covered Aggie sports for the Albuquerque Journal.

It was about filing stories on deadline, and it was before women reporters went into the locker room “so they used to bring out these giant guys wearing a towel and you had to interview them.”

She worked as a reporter for the Ruidoso News before going to UNM Law School, graduating in 1980. After that it was a year in private practice, some time as a ski bum and then to work for then-District Attorney Steve Schiff, “who was a wonderful boss, by the way.”

Home life

McGinn is married to Supreme Court Justice Charles Daniels, who she says won her heart by playing hard to get. They had been friends for years, but when they started dating he would drop her off and say thanks, good night and “shake my hand” even though at some point “I was trying all my best stuff.”

“It was so Machiavellian,” she says. “I was totally played.”

They don’t talk shop much at home, she says. He can’t talk about the court, and besides, life outside law can be much more interesting.

She is a frequent speaker around the country, likes to restore houses and has written one book and a draft of another. He is a known workaholic, plays in a rock band and races cars.

And, she says, his mom taught him how to dance.

They have three rescue dogs and spend a lot of quiet time “walking to Flying Star and going to movies. We see them all … even ‘Power Rangers.'”

They have a vacation home in Ruidoso, where they often gather with a bevy of kids and grandkids – both have children from previous marriages.

Her only regret about being married to a Supreme Court justice? “I can’t be involved in politics.”

No life quote

All in all, McGinn is in a good place and comfortable in her own skin.

“Life quotes” are all the rage these days, but when asked if she had a favorite she said, “What’s a life quote?”

Pet peeve?

“I’ve gotten to the point where not much bugs me.”

“Honestly,” she says, “my life to this point has exceeded anything I could have ever dreamed.”